I recently finished working as a facilitator for a rehabilitation program in prison. The program is called GRIP, which stands for Guiding Rage Into Power.

Today I thought I would share about this program and some of my experiences of teaching it for eleven years. I also thought it would be interesting to connect it to the teachings and messages we have learned from studying near-death experiences.

GRIP is an intensive fourteen-month program that helps inmates serving serious sentences (often life sentences) to understand themselves and their crimes, and to take accountability for the harm they have caused. It helps them do this by teaching them about victim impact and emotional intelligence, and by equipping them with tools to deal with deep-rooted feelings of grief, rage, and shame (so that they never hurt others again). Believe it or not, beneath most violence lie wells of grief, alienation, and unattended pain. And in order for people to reintegrate safely back into society after serving a long prison sentence, they have to be able to prove that they have changed and that they can control their emotions and impulses.

In our program, we believe people can change behaviors and become “safe” human beings again (i.e., committed to serving and helping others rather than causing harm) only by diving inward and learning about why it is that hurt people hurt people, and healed people heal people. In other words, we explore how attending to our own pain, hurt, and trauma enables us to take responsibility for the hurt or harm we’ve caused and stop the cycle of lashing out at others with it.

It turns out the personal pain we don’t deal with can become a poison that drives us to hurt others. (Important note: This hurt can take extreme forms, like murder, but it can also cause more subtle forms of harm, such as using insults and put-downs.)

So to get to the root of why humans resort to violence of any kind, we have to go deep into their history, their heart, and ultimately their soul.

Redemption

During one of our final classes in the program, we bring in victims or survivors of violent crime. We ask the prisoners to sit and listen to these survivors’ stories with respect. After they share, the prisoners can ask questions or share in response to what they’ve heard.

It can be a powerful and intense process, as often the criminal justice system keeps offenders and victims separate, many times for good reason. However, it is also common that the survivor or victim decides they would like to meet the offender. Why, one might ask? Sometimes the pain for the survivor is so intense—perhaps they lost a loved one in a murder or serious accident—that after years of grappling with the pain on their own, they decide that sitting face-to-face with the person who took their loved one’s life might actually lead to some form of relief from the pain.

While it may sometimes not help (or even be understandably overwhelming), many times this experience can bring tremendous healing to both parties, especially if the offender has done serious work on themself and takes full and complete accountability for their crime. It can allow the survivor to share their experience of pain, grief, and loss, to ask questions, and if they choose to, to listen to the offender about why they did what they did. Sometimes there is an apology or forgiveness given, but only if and when the victim feels ready.

Yet the way the criminal justice system is set up, even if both the victims and the offenders want to see and talk to each other, they are usually not allowed to.

For this reason, in GRIP, we bring in different survivors of violent crime—not those related to the inmates in our class—and this experience can provide a type of surrogate encounter and be incredibly powerful, especially when both sides have done significant healing work on their own.

On this day, I had the opportunity to bring in a young man and a young woman who had grown up with one or both parents incarcerated. Both of these young people had a parent who had committed a murder or other serious crime and consequently been sentenced to life in prison while they were still children.

It’s important to note that while many people might assume these young adults would harbor anger and hate for their fathers under these circumstances, it is actually quite common for there to still be a strong bond of love. Many children forgive such parents, especially if the parent has done serious self-work and healing, and has become someone who is no longer violent or angry.

Redemption, indeed, is quite possible for these families.

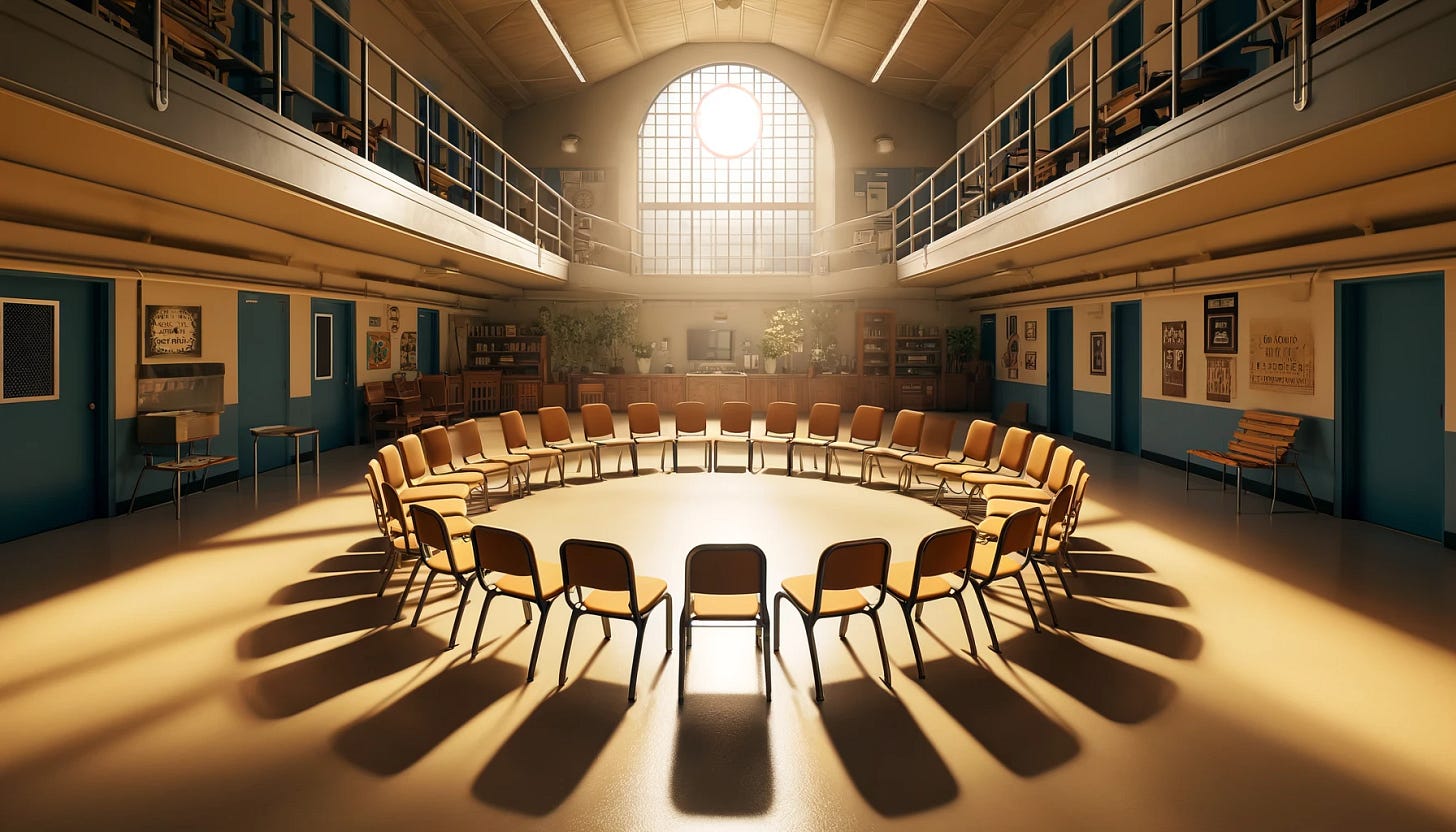

As our group of thirty-five circled up and did our mindfulness meditation, I noticed the prisoners looking uncertainly, almost hopefully, at our new guests. I could sense their excitement, their curiosity, but I could also see within the uncertainty looks of uneasiness and shame.

This was no small moment.

Most of the men in our group have children, and fatherhood is a common topic. The grief, the shame, the remorse for going to prison for committing crimes and therefore leaving their children—often babies and infants—alone with their mothers is painful to come to terms with and accept responsibility for. Such burdens can easily grow into nasty and vicious voices of self-judgment and self-hate. And loss of family—loss of connection and love—is a wound that heals slowly if at all.

I watched with bated breath as our guests, now in their early twenties, shared their experiences of childhood visitations in prisons, the pain of not being able to hug their father behind the glass, the alienation and shame of lying about the whereabouts of their parents to friends. The confusion. The anger. The refusal to reply to letters. The difficulty in understanding their feelings. The push and pull of attachment.

The young man broke down and cried as he described what it was like to lose his dad when he was three, and the subsequent difficulties of his childhood. I saw many men in our circle, heads in their hands, crying. Some quietly, some loudly. They simply listened and couldn’t stop the rising up of their own grief and pain. It was clear that there was a common experience being spoken aloud.

When the guests had shared and the inmates began to respond, it was completely still and silent in the room.

All eyes were on the man who was speaking. He broke down completely. His body shaking, the muscles in his face taut as he tried to maintain composure, he talked about what it was like to be pulled away from his family (his crime was committed in an attempt to protect his family from a violent situation). Especially painful was the fact that he had two sets of twin children who were young at the time.

He felt such grief and regret that I could see it in his body posture—most clearly when he lost the ability to speak and his chest heaved in silence. Other men murmured and nodded. The man sitting next to him simply put his hand on his back and kept it there.

As he was speaking, I noticed the guest—the young woman sitting next to me—was crying as well. I spoke, thinking aloud to the group, “Robbie, thank you so much for your tears. It’s as if you are speaking on behalf of everyone in here, all the prisoners, and the grief and pain of losing your children.”

He nodded silently, looking between me and the guest next to me, who was gazing back at him. Then I turned to her and asked if she would like to step in as a symbolic representative of all children who lose their parents to prison. She said yes.

So I asked her, “What would you like to say to them?”

What followed was so deeply moving that neither I nor hardly anyone in there could hold back tears. She spoke so tenderly, sharing her grief and pain, but also acknowledging and taking in his grief. Mostly they just cried together, both wiping their eyes, going in and out of eye contact, reassuring each other—when he was crying she would say, “It’s OK, I know, I know.”

It was as if in some invisible, nonverbal way she was giving him permission and acceptance to feel deeply. Feel all of it. Prison is a hard place to feel. And in some way she was giving him forgiveness. And he was giving her his pain, his grief, and his remorse. It was beyond words, though. It was a somatic, energetic exchange, like sponges dried from separation finally coming into life-giving contact with water.

I simply don’t know how else to describe it.

By the time we stood holding hands in a circle at the end of the group, it was clear that something deeply healing had taken place. The air felt clear and even the cramped classroom felt wide open and spacious.

Our Native American facilitator, who had been witnessing this all in silence, spoke of the work we had done that day as sending prayers into the future—seeding future generations and sending ripples in all directions. He spoke quietly but deeply, saying that the healing of that day was not only for one person or one group but for everyone, around the world. For we are all interconnected.

How does this connect with near-death experiences?

Well, when we listen to NDE accounts, a core theme is that of a life review. In these life reviews, it is the experiences of kindness, compassion, and generosity that are highly valued on the Other Side. Acts such as forgiveness, nonjudgment, and the expressing of love are what becoming human and living on Earth is all about.

Down here on Earth it is easy to judge, to hold resentments and bitterness. It is easy to get stuck in fear, anger, and hurt. These are emotions that can pull us down into a revolving cycle of hurt and pain.

The phrase “hurt people hurt people and healed people heal people” refers to this very theme. When we are hurt, it’s all too easy to hold onto our pain, obsess over it, amplify it, and nurse our hurts and demonize those who caused us the pain. This will only make us more likely to suffer and cause us to lash out and hurt others as well.

The teachings from NDEs, however, point out that when we integrate and let go of our hurts and resentments, we are then more able to bring an open heart to others and still act out of a place of love and generosity.

Jesus of Nazareth is most famous for loving others, even those who were crucifying him. To turn the other cheek is to put down our hurts, our egos, and our anger, and to instead meet others (even those who have hurt us or our loved ones) with even-keeled equanimity. An important note here is that we can still hold boundaries and discipline while having an open heart (i.e., if someone has committed violent crimes we can keep them in prison, or if someone treats us badly we can keep them out of our life, for example).

Forgiveness also doesn’t mean the act of harm we underwent was OK.

If someone hurts me or my family, I can unequivocally hold that act to be immoral, unethical, and wrong. They can be punished for it, too. But the person themselves, the soul who has lost touch with themselves and their spiritual core, they can still be worthy of love and compassion.

The highest moral bar that Jesus and Buddha taught was meeting all anger and hate and hurt in the world with love and compassion. It’s about transforming the poison of resentment and hate within ourselves. I have met survivors of violent crime who, even when the person who caused the harm had been locked away in prison for decades, had no peace as they were filled with poisonous anger and hate that lingered, grew, and twisted their insides.

That is no way to live, as it is the life of a prisoner.

In a life review, we will relive and be presented with all the ways we held onto our pain and anger—and all the missed opportunities for forgiveness, patience, and love.

On the other hand, there are those who have caused tremendous harm to others, without any awareness or remorse. Those who have not undergone the deep soul journey of awakening and healing (which requires the tremendous courage of diving into one’s own hurt, grief, and trauma) are likely to find themselves experiencing a very painful life review.

Certain NDE accounts tell us about the horror and shame people felt at reliving even minor wrongs and harms they had caused in their lives. One can only imagine what kind of life review someone experiences after committing serious crimes and violence without any kind of remorse or atonement.

What happens after such a life review, I cannot say, although I am sure many people have beliefs about what happens. I do believe karma has a role to play and that such actions require equal and opposite reactions to be completed and absolved.

By watching people who have caused great harm (the men in blue in prison), as well as those who are survivors of violent crime, I have realized that more than anything, an awareness of the soul and of the spiritual realm is the healing antidote to suffering.

There is a reason that the Christian themes of redemption and atonement are so pervasive and profound. They are archetypal themes that speak to this kind of spiritual healing.

While on Earth none of us know the full story. We all judge, and yet we are likely to be confronted with the many unwarranted judgments in the hereafter. Many of us have hurt others, and we know it when we feel sorry for what we’ve done. I believe we are all human in that way, and that we leave it to God to do the judging.

I will say that my eleven years in prison have taught me to have more humility. I cherish and feel grateful to have had the opportunity to do this healing work with so many men and women.

I have now stepped away from that work and more fully into growing Coming Home with my brother Eliot. We believe that NDEs and their implications can provide another layer of healing for everyone in the world, as it contextualizes our human experience in something much, much larger.

If you enjoy what we are doing at Coming Home, feel free to subscribe and share with others.

Until next time!