Originally published June 25, 2023

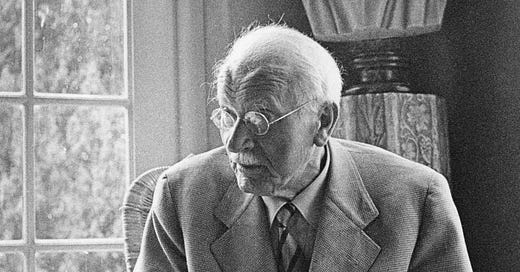

Many people don’t know that the famous Swiss psychologist Carl Jung had a near-death experience, and that it radically impacted his life.

Jung, the one-time heir to Sigmund Freud and early founder of the field of psychology, is best known for coining popular phrases such as the “collective unconscious,” “the shadow,” and “synchronicity.” He helped to build the foundation of research and study for the modern field of psychology and psychoanalysis.

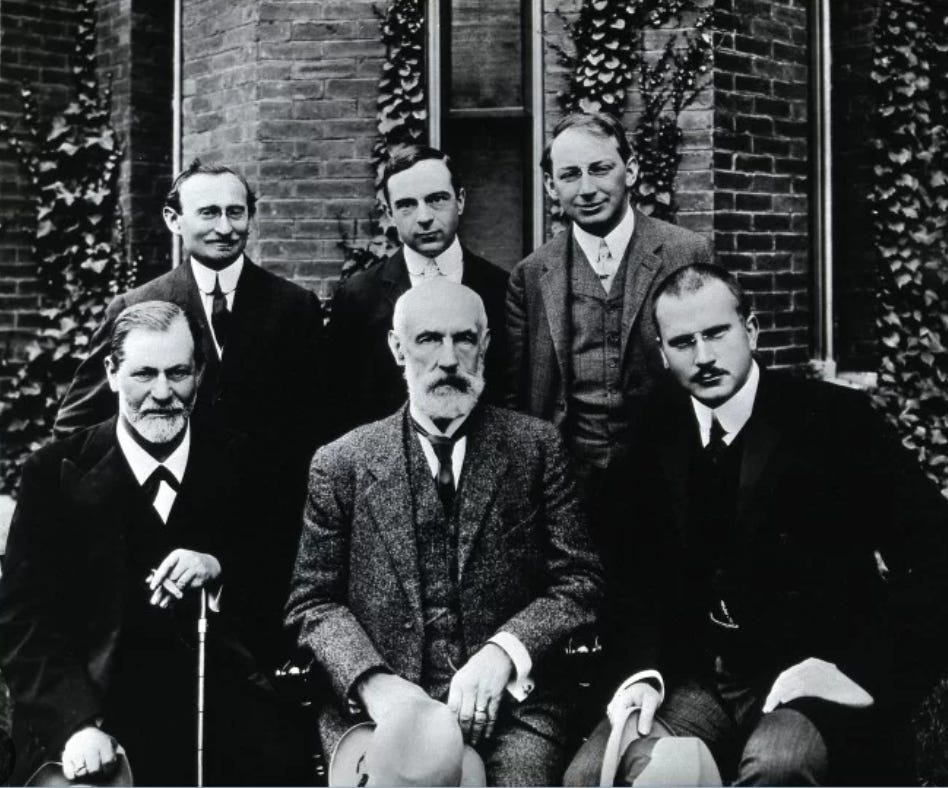

Sigmund Freud (the original founder of psychoanalysis) became so enamored of the young Swiss prodigy that he began to work with him, co-authoring papers and developing the theories of psychoanalysis. Freud eventually asked Jung to become president of his International Psychoanalytical Association in 1910, just as psychoanalysis was starting to sweep across Europe, exploding in popularity.

Freud took the role of father figure and mentor to the younger Jung.

But there was a major difference between Jung and Freud. It was a fundamental theoretical difference, and it grew so large that it caused a permanent break between the two men. After a decade of intense and world-altering collaboration, the two intellectual giants parted ways and ceased all communication.

What was the theoretical difference that caused this painful break?

Jung had become increasingly fascinated with the spiritual and metaphysical world of comparative religion and mythology. He would point out that the very word psychology came from the Latin root psyche, which means “soul.”

Literally, the word psychology means “the study,” or “care” of, “soul.”

Jung saw the human mind—or psyche—as embedded within the larger psyche of the collective, which included the vast realm of the transpersonal or mystical worlds, which he often called the numinous. God, angels, saints, spirits, and beings of various kinds were perfectly at home in his psychology, because he understood that beyond the physicality of gross matter existed Spirit, in all its myriad forms.

He even wrote his doctoral dissertation on the psychology of mediumship and séances. He was curious about the “occult”—a catch-all phrase used to describe a wide variety of spiritual, mystical, and supernatural phenomena. It is worth noting that many people associate the term “occult” with dark or “demonic” magic and witchcraft; but in reality this term does not have a negative association. It simply refers to the study of phenomena that are invisible and mysterious to the modern scientific materialist and are therefore deemed magical.

Freud could not tolerate this because, as a scientist and doctor, he believed that such spiritual phenomena were naïve and superstitious. Freud was a pragmatist and an atheist at heart. Jung was a philosopher, a theologian, and a mystic at his core.

Thus destiny was to pull them apart and send them in different directions; each to develop complementary but fundamentally different systems of psychology.

Jung had had mystical experiences, even from a young age. And these experiences influenced his system of psychology.

In his memoir Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung shares candidly about his encounters with spirits, ghosts, and poltergeists. But more privately, he had been uncovering profound secrets in the mystical worlds of Kabbalah, alchemy, and mythological symbolism. He had a deep interest in the world’s religions, and in particular, forms of Gnosticism and Christianity.

Yet despite these interests, Jung became world famous for his psychoanalytic system of psychology. He was known to the world abroad as a scientist of the mind, a doctor, and a healer. People flew across the world to be treated by him in his private practice.

Jung and Alcoholics Anonymous

Another little-known fact is that Jung inadvertently helped the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and the entire twelve-step program of recovery. When Jung was an old man in his late eighties, he received a surprise letter from Bill Wilson, the co-founder of AA, who explains the story. It turns out that after trying to treat a severe alcoholic by the name of Rowland Hazard, Jung decided nothing short of a spiritual experience would be able to heal him of his alcoholism. He said later about Hazard, “His craving for alcohol was the equivalent, on a low level, of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness, expressed in medieval language: the union with God.”

He believed that underneath most addictions, certainly those of drug and alcohol addictions, is a secret search for spiritual wholeness and a remembrance of the soul. Perhaps there is a cosmic wink in the irony that the term “spirits” refers to alcohol, when truly the alcoholic is looking for Spirit.

So it was that Jung recommended Hazard find a spiritual community with the instruction to pray and meditate in a religious environment. Lo and behold, Hazard had a spiritual experience that upended his entire life and led him to achieving sobriety for the rest of his life. Hazard was involved in that religious community for many years, and through this community Bill Wilson found himself surrendering in desperation—as alcoholism was destroying his life. After praying aloud, “If there is a God, let him show himself,” he suddenly had what he calls a conversion experience. He says of this experience in his letter to Jung, “My release from alcohol obsession was immediate. At once, I knew I was a free man.”

In the years that followed, Bill Wilson co-founded AA, which through its many twelve-step programs—addressing addictions as diverse as drugs, gambling, and eating disorders—has helped millions of people around the world.

Jung’s Near-Death Experience

In 1944, Jung was nearing seventy years of age. One day during the winter, he slipped on some ice and broke his foot. While he was in the hospital, he had a heart attack. Unresponsive for days, the doctors fought for his life.

During his heart attack, he had a profound experience—his near-death experience—which he shared in his memoir. This was, of course, many years before Raymond Moody established the concept of near-death experiences.

After Jung died, he felt he ascended up into space. In his own words:

It seemed to me that I was high up in space. Far below I saw the globe of the Earth, bathed in a gloriously blue light. . . . My field of vision did not include the whole Earth, but its global shape was plainly distinguishable, and its outlines shone with a silvery gleam through that wonderful blue light. I knew that I was on the point of departing from the earth . . .

Later I discovered how high in space one would have to be to have so extensive a view—approximately a thousand miles! The sight of the Earth from this height was the most glorious thing I had ever seen.

Something new entered my field of vision. A short distance away I saw in space a tremendous dark block of stone, like a meteorite. It was floating in space, and I myself was floating in space . . . an entrance led into a small antechamber. To the right of the entrance, a black Hindu sat silently in lotus posture upon a stone bench. He wore a white gown, and I knew that he expected me. . . . Innumerable tiny niches, each with a saucer-like concavity filled with coconut oil and small burning wicks, surrounded the door with a wreath of bright flames.

As I approached the steps leading up to the entrance into the rock, a strange thing happened: I had the feeling that everything was being sloughed away; everything I aimed at or wished for or thought, the whole phantasmagoria of earthly existence, fell away or was stripped from me—an extremely painful process. Nevertheless something remained; it was as if I now carried along with me everything I had ever experienced or done, everything that had happened around me. I might also say: it was with me, and I was it.

I consisted of all that, so to speak. I am this bundle of what has been and what has been accomplished. This experience gave me a feeling of extreme poverty, but at the same time of great fullness. There was no longer anything I wanted or desired . . . I had everything that I was, and that was everything.

Something else engaged my attention: as I approached the temple I had the certainty that I was about to enter an illuminated room and would meet there all those people to whom I belong in reality. There I would at last understand—this too was a certainty—what historical nexus I or my life fitted into.

I would know what had been before me, why I had come into being, and where my life was flowing. My life as I lived it had often seemed to me like a story that has no beginning and end. I had the feeling that I was a historical fragment, an excerpt for which the preceding and succeeding text was missing.

My life seemed to have been snipped out of a long chain of events, and many questions had remained unanswered. Why had it taken this course? Why had I brought these particular assumptions with me? What had I made of them? What will follow? I felt sure that I would receive an answer to all the questions as soon as I entered the rock temple. There I would meet the people who knew the answer to my question about what had been before and what would come after.

While I was thinking of these matters, something happened that caught my attention. From below, from the direction of Europe, an image floated up. It was my doctor, or rather, his likeness—framed by a golden chain or a golden laurel wreath. I knew at once: “Aha, this is my doctor, of course, the one who has been treating me. But now he is coming in his primal form.”

As he stood before me, a mute exchange of thought took place between us. The doctor had been delegated by the Earth to deliver a message to me, to tell me that there was a protest against my going away. I had no right to leave the Earth and must return. The moment I heard that, the vision ceased.

I was profoundly disappointed, for now it all seemed to have been for nothing. The painful process of defoliation had been in vain, and I was not to be allowed to enter the temple, to join the people in whose company I belonged.

Jung returned to his body, and slowly began to recover from his heart attack. But it was not easy. Like many other people who have had NDEs, there can be a long process of integration. It often includes feelings of depression and despair as one adjusts to being back in the human realm with a physical body, which can feel painfully restrictive after an experience of tasting our infinite and radiant true nature.

Jung goes on to say that:

In reality, a good three weeks were still to pass before I could truly make up my mind to live again. I could not eat because all food repelled me. The view of city and mountains from my sickbed seemed to me like a painted curtain with black holes in it, or a tattered sheet of newspaper full of photographs that meant nothing.

Disappointed, I thought, “now I must return to the ‘box system’ again.” For it seemed to me as if behind the horizon of the cosmos a three-dimensional world had been artificially built up, in which each person sat by himself in a little box.

And now I should have to convince myself all over again that this was important!

Life and the whole world struck me as a prison, and it bothered me beyond measure that I should again be finding all that quite in order. I had been so glad to shed it all, and now it had come about that I—along with everyone else—would again be hung up in a box by a thread.

This sense of coming back to his life in a world that felt like a “box system” held by a thread was a profound one. It took him three weeks to decide to live again, as he struggled to convince himself “all over again that this [human world] was important.” It wasn’t easy, even for such a successful and worldly man as Jung.

After this experience, he dove even more deeply into the mystical teachings of Christianity and alchemy, convinced that this mundane world of gross physical matter was a mere dream and that on the other side of the veil lived the true world of spiritual and astral phenomena. That, he believed, was the real world, while this drama, this play on earth, was the “box system,” the amphitheater in which we must play the roles of our human lives.

Jung taught that our psyche comprises both the personal unconscious, shaped by our individual experiences, and the collective unconscious, which contains inherited patterns from our ancestors. He believed the collective unconscious contained images and forms that are eternal, and which we all instinctively know.

He called these images archetypes and believed he saw some of them during his NDE. For example, he believed the Hindu man he saw with crossed legs was not only his “higher self” but was also the “God Image,” the ultimate archetype of the numinous dimension; that is, the Holy.

Why does Jung and his psychology speak so deeply to modernity?

Because we are parched dry. We are told we humans are accidental life forms sprung from the meaningless collisions of ice and rock. That we have no purpose or inherent meaning. That all we have is this short lifespan to procreate and have some fun if we are lucky, and after that we disappear from the cosmos like some faintly flickering firefly on a summer night.

But that isn’t true.

And an intellectual and philosophical genius like Jung could lay down with principled logic and erudite research why that isn’t so. He harkens back into history, and at its roots his psychology draws from the sophisticated metaphysics of the ancient Greeks, the passion of the Jewish prophets, the love and compassion of the Christian saints, and the mysticism of the alchemists. He collects the tapestries of the world’s mythologies and religions and weaves together the symbols and archetypes to unveil a universal and perennial psychology that still speaks to the modern humans of today.

He succeeded in creating a psychology that could help people grapple with their human neuroses and day-to-day sufferings—but he could also speak to the soul.

He believed that we are spirits having a human experience, not humans having a spiritual experience.

Thank you for this. Perhaps both are true at once, the eternal holding of opposites: we are humans having a spiritual experience AND we are spirits having a human experience.

Yes having his experiences out there, right along side his respected standing in the intellectual community has been such a comfort to me. I'm not going crazy...or at least not JUST crazy. I'm seeing more... and I'm not the only one to have done so, so it must have some reality to it even if it challenges what we generally mean by "reality".